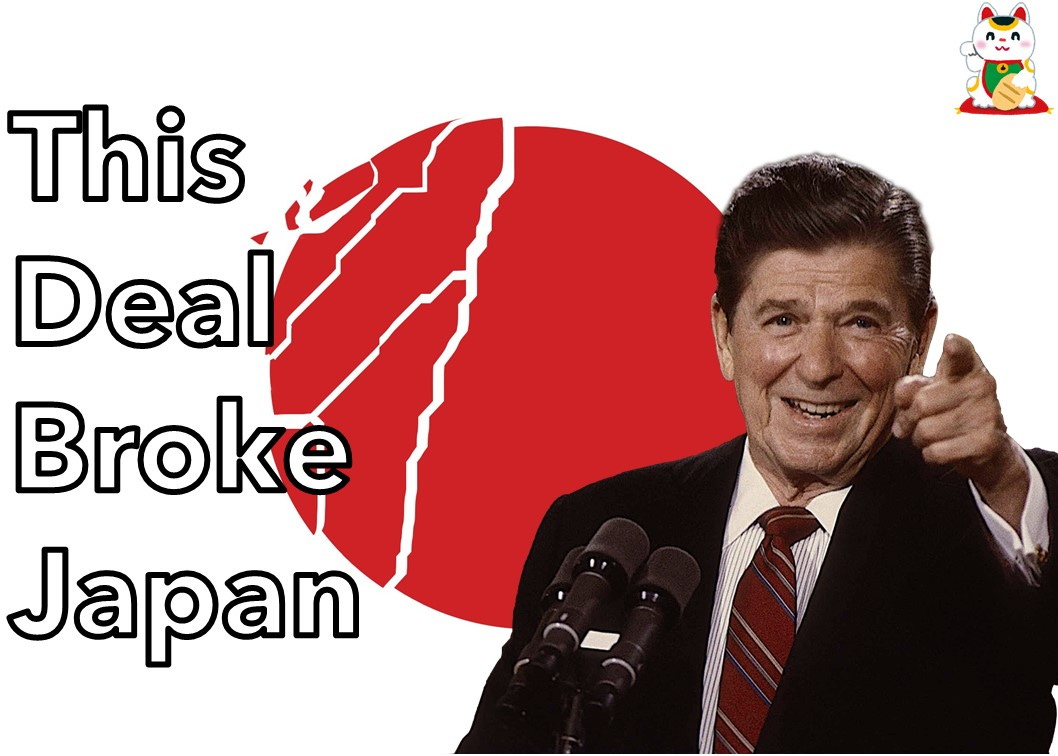

The Plaza Accord: Reagan's Role, USD Collapse & Japan's Fall

Join me as I delve into the Plaza Accord of 1985, the agreement that shook the global economy and marked the beginning of Japan's economic collapse

Introduction

The Plaza Accord. Just the mention of these words is enough to send shivers down the spines of economists and policymakers around the world. It was one of the biggest single events that have shaped how the world sees Japan. And I have undertaken the daunting task of examining it.

To my dear readers and fellow members of KonichiValue, I want t…