Disclaimer: This report is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice. All investments involve risk, including the loss of principal. I, Rei Saito, may hold positions in any securities mentioned.

I have tasked myself with finding the greatest investor in Japan, and the search did not take long.

While there are others who have achieved fame in the retail space, most notably the brash and vocal CIS, there is only one undisputed god of the Japanese investing scene.

His name is Takashi Kotegawa, but the financial world knows him simply as B.N.F.

He is the man who turned his student savings of roughly 1.6 million yen into a fortune exceeding 30 billion yen ($272 million).

That’s a 1,874,900% total return!

He is the man who managed to make over 2 billion yen ($18.2 million) in 10 minutes during the most infamous trading mistake in Tokyo Stock Exchange history.

He is the man who bought a commercial building in Akihabara with cash simply because he had run out of things to do with his money.

Kotegawa grants almost no interviews. He has no social media presence. He does not sell courses. He does not want your money. He wants only to trade.

And to understand his life since he went silent in 2020, I have compiled the available traces of his career: Old 2-chan forum posts, his few media appearances from 2006, public tax records, and the analysis of the Japanese trading community.

This report is his story….

Part I: The Death of the Salaryman

To understand Kotegawa, I must first paint the picture of the Japan he emerged from.

The year was 2000. The world’s biggest bubble had burst a decade prior, and the Nikkei 225 was a graveyard of optimism. The great Japanese dream of the salaryman, a stable, respectable career with lifetime employment that had underpinned the social contract since 1945, was dying. Japan was sliding into the deflationary abyss that would come to define its “Lost Decades.”

For the generation coming of age in the late 1990s, the corporate ladder looked less like a path to security and more like a trap. The “shinjinrui” (new breed) of young Japanese were disillusioned. They saw their fathers sacrifice their lives for corporations that were now discarding them. They looked for an escape.

The Digital Big Bang

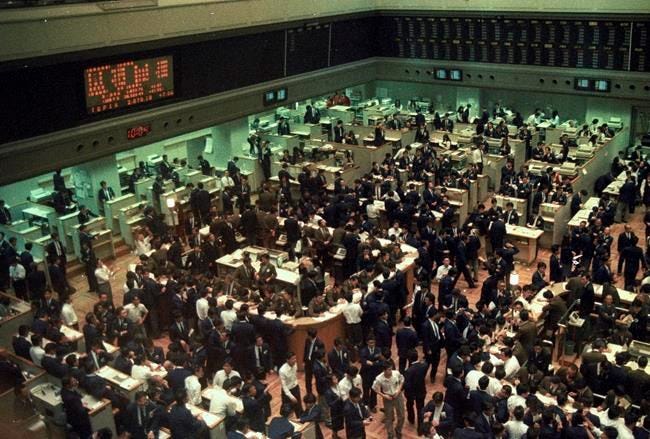

However, a quiet revolution was taking place beneath the surface of this economic stagnation. The Japanese government, desperate to revitalize the financial sector, executed the “Financial Big Bang.” A critical component of this was the liberalization of brokerage commissions in October 1999.

Before this moment, trading stocks was a rich man’s game. It was gated by high fees and telephone orders. You had to call a broker. You had to pay a significant percentage of your trade execution. It was slow. It was inefficient. It was exclusive.

Suddenly, online brokers like Matsui Securities, Rakuten Securities, and E*Trade Japan emerged. They offered low latency and, crucially, low commissions. They opened the gates of the Tokyo Stock Exchange to the general public.

It was the dawn of the “Net Trader.” Thousands of young men retreated to their bedrooms. They armed themselves with PCs and high-speed internet connections.

They were the first generation to see the market not as a mechanism for capital allocation, but as a massive multiplayer online game played for real money.

Takashi Kotegawa was one of them.

Part II: The Birth of B.N.F.

Takashi Kotegawa was born on March 5, 1978, in Ichikawa, Chiba Prefecture. His background is aggressively ordinary. This is important. No math prodigy from a prestigious academy. No heir to a financial empire. He was a student at Nihon University, an average university at best, enrolled in the Faculty of Law.

In a parallel universe, Kotegawa graduates. He passes the bar. He becomes a salaryman lawyer. He works 14-hour days for a steady paycheck. He commutes on the Tozai Line. He retires at 65.

In this universe, he found the stock market.

The year was 2000. Kotegawa was 21 years old. He had saved approximately 1.6 million yen (roughly $13,000 at the time) from rigorously saving money from his part-time jobs.

The Victor Niederhoffer Connection

Hooked by the relentless ad campaigns of the new internet trading era, Kotegawa entered the market just as a historic downturn began. The US Dot-com bubble had just burst, and it evaporated trillions of dollars in wealth, creating a global contagion that dragged the Nikkei down to levels not seen in nearly twenty years.

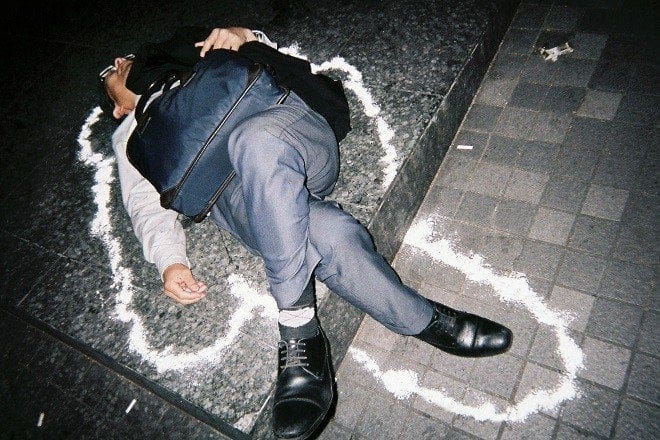

While panic selling turned the markets into a slaughterhouse, Kotegawa quietly opened his account.

Needing a handle for the internet forums where traders gathered to share ideas, he chose “B.N.F.” It was a phonetic error; he intended to use “V.N.F.” to honor Victor Niederhoffer, but because the Japanese language treats “V” and “B” almost identically, the misspelling stuck.

The choice was telling. Niederhoffer was an eccentric American squash champion and George Soros partner, but his edge was purely statistical. He believed that markets followed strict statistical rules, specifically, that if an asset price deviated too far from the average, it was mathematically bound to snap back. This approach made him one of the most successful fund managers on Wall Street.

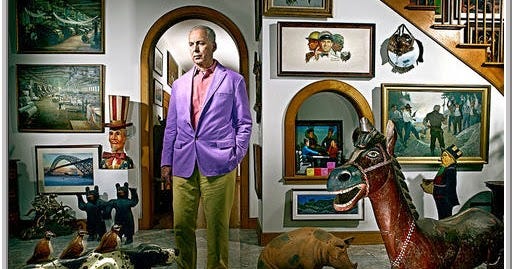

But in 1997, the math stopped working. Niederhoffer bet heavily that the Thai market had fallen too far and had to rebound. It didn’t. In a single day, his fund was wiped out. He lost $130 million in equity, erased his clients’ savings, and was eventually forced to auction his personal art collection just to pay the bills.

Now why would a young student name himself after a man who lost it all?

I believe Kotegawa saw the distinction between the method and the execution. He adopted Niederhoffer’s core philosophy: Buying the panic dip because the math says it must bounce, but he treated the 1997 crash as the ultimate lesson in risk management: Do not trade on borrowed money!

By the time his graduation approached in 2001, the ¥1.6 million ($13,000) he had scraped together from years of part-time work had ballooned to ¥61 million (~$500,000). That represents an explosive 3,712% portfolio growth in just a single year.

He calculated that the opportunity cost of finishing school was simply too high. Every hour in a law lecture was costing him millions. So, with only a few credits remaining, he decided to drop out.

Part III: The Art of Catching Falling Knives

I have analyzed hundreds of trading strategies. Most are absolute nonsense. They are rigged to look perfect on past data just to hook gullible subscribers. Kotegawa’s is different.

It is brutally simple. It is also psychologically impossible for 99% of people to execute.

Kotegawa’s Trading Strategy

Kotegawa made his initial fortune between 2000 and 2004. These were dark years for Japanese equities. The Nikkei 225 slid from 20,000 to under 8,000.

Most retail investors try to pick bottoms based on hope. They buy a stock because it has fallen 50% and they think “it cannot go lower.”

It usually goes lower.

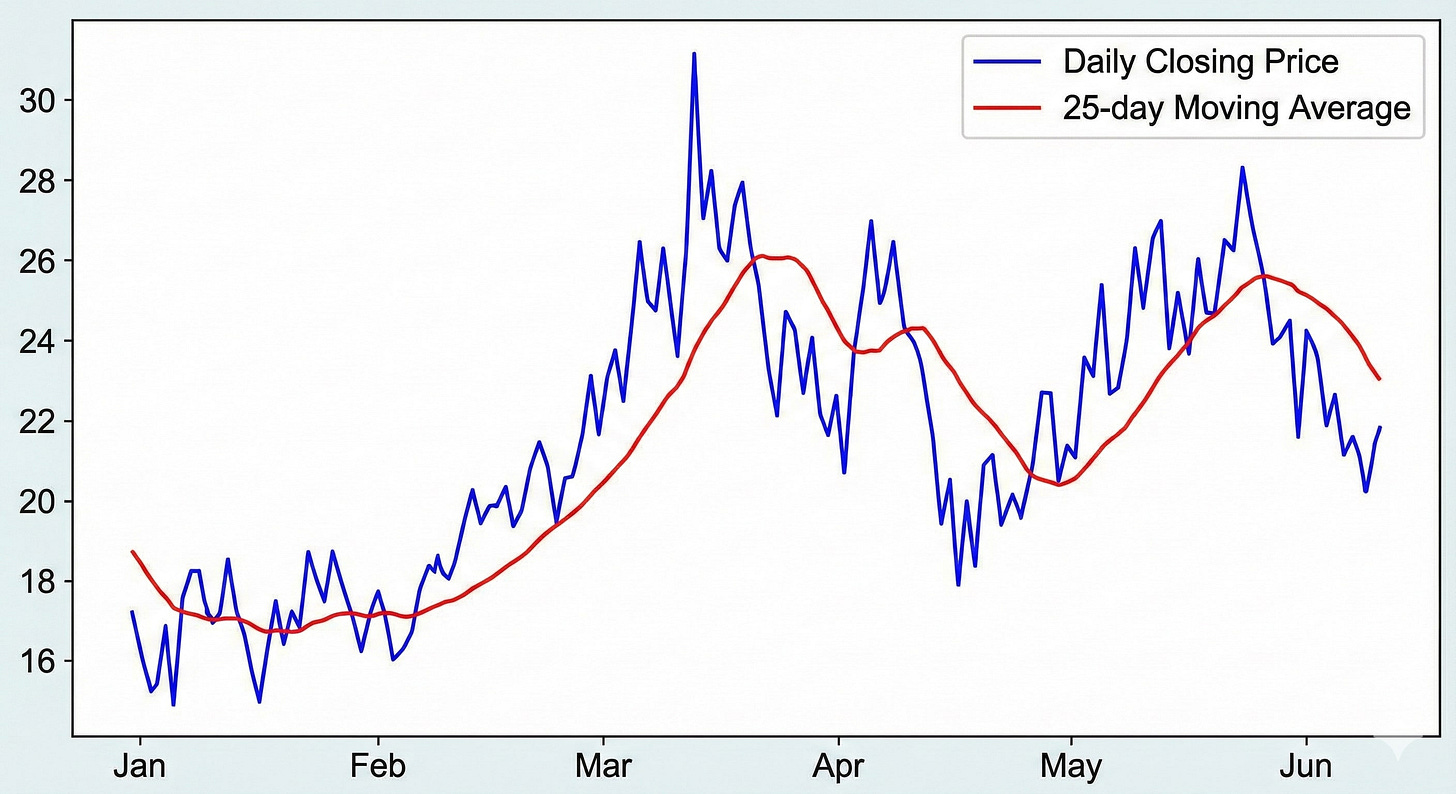

Kotegawa inverted this logic. He did not buy because he liked the company. He bought because the selling was emotional. He waited for the selling to reach a mathematical breaking point, measured by the 25-day Moving Average Divergence (kairi-ritsu in Japanese).

Think of the 25-day Moving Average (MA) as a rubber band. When the price pulls too far away from this average, it stretches tight. Eventually, it has to snap back.

The Sector Rules

Kotegawa knew one number didn’t fit all. A utility stock doesn’t stretch like a tech stock. Through obsessive watching, he found the “snap point” for every industry.

Based on his old posts, these were his rough rules (measured against the 25-day MA):

Pharmaceuticals: Buy at a 5–10% drop.

Electric Appliances: Buy at a 10–15% drop.

Food / Retail: Buy at a 15–20% drop.

Tech / Internet: Buy at a 20–30% drop.

Speculative / Penny Stocks: Buy only after a 30–50% drop.

When a stock crashed past these lines, Kotegawa struck. He was catching falling knives.

But the genius wasn’t the entry; any fool can buy a crash. The genius was the exit.

As soon as the stock bounced, often just 2% or 3%, he sold. He didn’t wait for a full recovery to the moving average. He grabbed the “dead cat bounce” and got out.

He repeated these small wins thousands of times.

By the end of 2004, he had made his first billion yen (¥1.1 billion, or roughly $10 million). He had turned his starting cash into a 690x return.

Part IV: How to Make Two Billion in Ten Minutes

Every superhero has an origin story. Every trader has a defining trade.

For George Soros, it was breaking the Bank of England.

For Takashi Kotegawa, it was the Mizuho “Fat Finger” error of December 8, 2005.

This event is the reason I am writing this biography. It is the moment Kotegawa transcended from “successful day trader” to “national legend.”

The Error

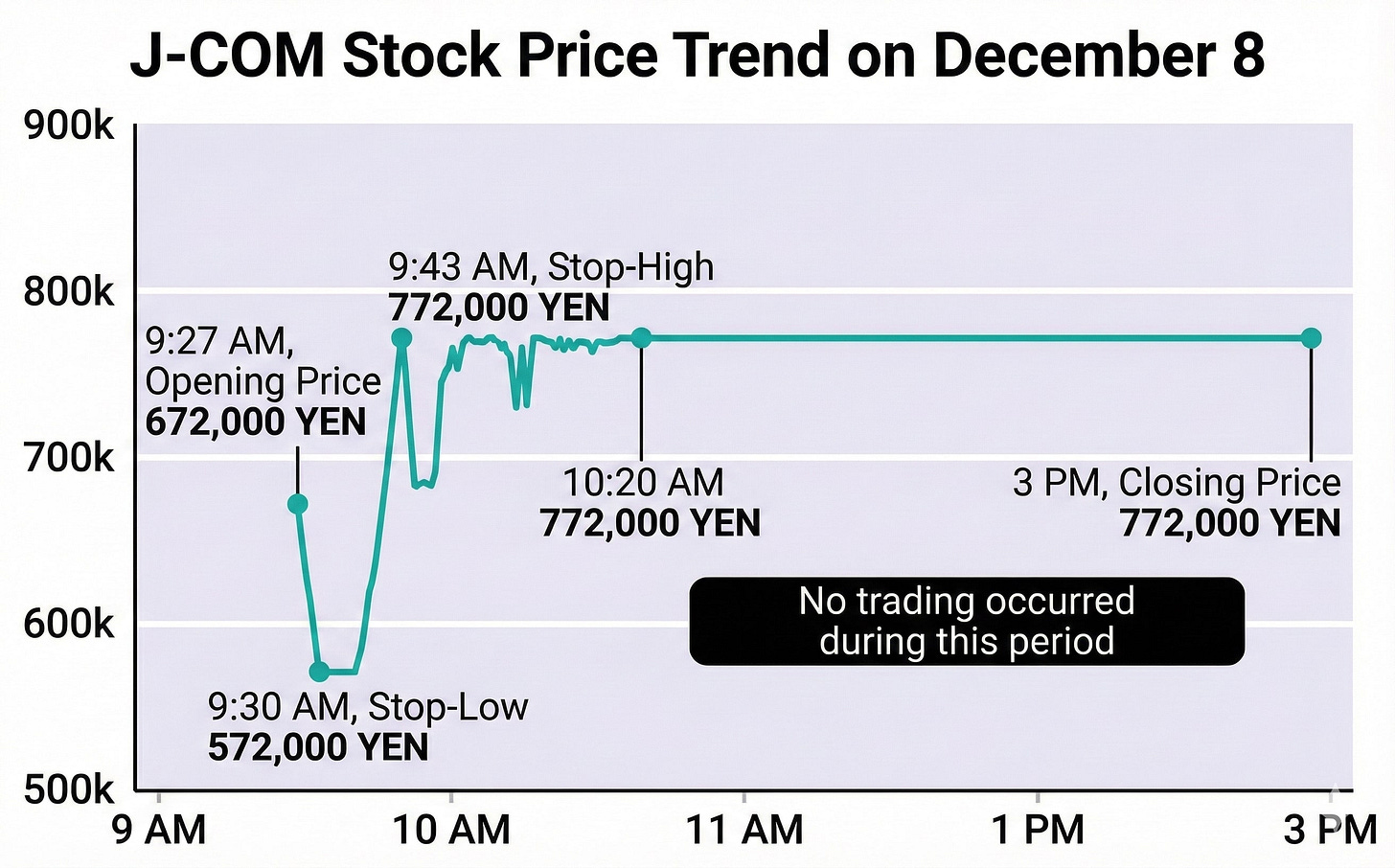

The date was December 8, 2005. J-Com Co., Ltd., a recruitment service company, was listing on the “Mothers” (small-cap) board of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. It was supposed to be a routine IPO.

At 9:27 AM, a trader at Mizuho Securities received an order from a client to sell 1 share of J-Com for 610,000 yen.

The trader made a typographical error. It was a simple slip of the keyboard. He entered an order to sell 610,000 shares for 1 yen.

The computer system at the Tokyo Stock Exchange did not catch the error. There were no circuit breakers for this specific type of volume discrepancy at the time. The order went live.

To put this in perspective, J-Com only had 14,500 outstanding shares. Mizuho had just offered to sell forty-two times the entire existence of the company for less than a penny per share.

The Recognition

The stock price collapsed instantly.

Most traders stared at their screens in confusion. Was it a system glitch? Was the company bankrupt? Was it a fraud? Fear paralyzed the market.

Kotegawa did not freeze. He saw the anomaly. He did not know why it was happening, but he knew the math was impossible. He knew that 610,000 shares could not exist.

He bought.

He bought with both hands. He bought 7,100 shares.

Remember, there were only 14,500 shares in existence. Kotegawa had just purchased nearly half of the company’s float in a matter of seconds.

Other sharks began to circle. The famous Japanese day-trader CIS, Kotegawa’s friend and rival, also bought, securing about 3,300 shares.

Between them, these two kids in their bedrooms now owned the majority of a newly listed public company.

The Exit

Mizuho Securities realized the error. Panic ensued on the trading floor. They tried to cancel the order. The Tokyo Stock Exchange system did not allow the cancellation because their technology was so outdated. The order stood.

Desperate to cover the short position they had accidentally created, Mizuho began buying back the shares at any price. They had to close the hole they had dug.

The price rocketed.

Kotegawa sold. He dumped his shares into the frantic buying pressure of the very bank that had caused the crash.

By the end of the day, Kotegawa had netted a profit of approximately 2.2 billion yen (roughly $20 million).

He did this in roughly ten minutes

The Aftermath

The incident became known as the “J-Com Shock.” It cost Mizuho Securities roughly 40 billion yen. The head of the Tokyo Stock Exchange eventually resigned. It was a national scandal.

Kotegawa, however, was the face of the incident. The media dubbed him “J-Com Man.” He was 27 years old. He had made more money in ten minutes than the average Japanese worker earns in ten lifetimes.

When asked about it later, he simply said that he was “lucky” and that “anyone could have done it”.

This is false humility. Thousands of professionals saw the same screen. Only Kotegawa acted with that size and speed. He had prepared his mind for years to recognize anomalies, and when the biggest anomaly in history appeared, he did not hesitate.

Part V: The Curse of Scale

By 2008, Kotegawa’s assets had ballooned to over 21 billion yen (approx. $200 million). He was one of the wealthiest individuals in Japan, and he was still under 30.

The Problem of Scale

Success brings its own problems. When you have 100 million yen, you are a speedboat. You can enter and exit trades instantly. When you have 20 billion yen, you are an oil tanker.

Kotegawa began to move the market. If he tried to buy a small-cap stock, his own buying pressure would drive the price up, destroying his entry price. If he tried to sell, he would crash the stock.

He was forced to trade only the most liquid large-cap stocks: Softbank, Toyota, Nintendo, and the mega-banks. He had to lengthen his holding periods. He couldn’t snatch quick pennies anymore. He had to hold stocks for days.

What is so funny about his trading strategy is that he had zero interest in the actual businesses. In a rare TV interview, He admitted he had no clue what the companies he traded actually did, nor did he care about their earnings guidance. His only reality was the line on the chart.

Part VI: The Lifestyle of a Monk

Most billionaire biographies are catalogues of excess: yachts, vineyards, and private jets. Kotegawa’s list is blank.

This is the “quirk” that makes him a cult figure in Japan. In a culture that prizes humility, he is the monk of the market.

He has exactly one indulgence: A 400 million yen condo in Tokyo.

Yet, visitors (the few television crews who were allowed in around 2006) reported that the apartment was practically empty. There was no art on the walls. No designer furniture. Just the trading station with its multiple monitors.

Allegedly, he did buy his parents a Toyota Crown Majesta, the ultimate symbol of conservative Japanese success, but he doesn’t drive. He still takes the bicycle.

His biggest splurge, famously, was buying two Nintendo Wiis. One can assume he played them alone.

His diet consists almost exclusively of cup ramen and convenience store onigiri. He claims that eating a large meal makes him sleepy, which slows his reaction time. He avoids caffeine because it makes him jittery.

He famously said, “If you care about the money, you cannot make the right decisions.” He views money as a score in a video game.

Thinking about what money can buy invites emotion, and to Kotegawa, emotion is the enemy.

Part VII: The Lehman Crisis

The year 2008 was a test of fire for everyone. Kotegawa was not immune.

The Lehman Loss

In September 2008, Kotegawa made a rare misstep. He bet on the survival of Lehman Brothers. He bought the stock, assuming the US government would bail it out as they had done with Bear Stearns.

They did not. Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy.

Kotegawa lost approximately 700 million yen (roughly $7 million at the time).

In a rare display of emotion, he admitted to punching his computer monitors. He broke two of them. It is the only recorded instance of him losing his temper.

However, what defines him is not the loss, but the recovery.

In October 2008, right in the heart of the crisis, Kotegawa made a move that shocked the market.

He paid cash, approximately 9 billion yen, for a commercial building in Akihabara. The building was known as “Chomp Chomp Akihabara” at the time (it is now known as the AKIBA Cultures ZONE). The building was a 6-story hive of maid cafes and anime shops.

As the real estate market was collapsing, cash was king. Kotegawa, that had piles of cash finally used some to buy a distressed asset in Akihabara, the holy land of otaku culture.

It was the perfect hedge. As a fellow Otaku himself, he knew the building was undervalued. He knew he couldn’t day trade 20 billion yen forever, so he swapped volatility for rent. For ten years, he earned a massive yield that required zero mouse clicks.

By 2018, rumors suggest he sold it for 12 billion yen, capturing a 30% gain on top of the rent.

Part VIII: Where is He Now?

Since the sale of the Akihabara building, Kotegawa has largely vanished.

He appeared in the “shikiho” (Japan Company Handbook) substantial shareholder lists for a few years, popping up on the registries of companies like JVC Kenwood or Oricom. But recently, his name has become scarce.

There are rumors. Some say he fled to Singapore to escape taxes. Others claim he shifted to private equity. But that contradicts his deep attachment to his home turf.

The reality is likely simpler. As his friend and rival CIS once said: “He doesn’t trade for money. He trades because it is the only thing he knows how to do.”

He is almost certainly still in Tokyo, sitting in a different high-rise, likely worth well over 30 billion yen. He has probably switched to global macro or index futures, where his massive size doesn’t break the market.

He is a ghost. But every time the market crashes, every time there is a panic, every time the charts turn red and the world is screaming “Sell!”, I know he is there.

Appendix: The Kotegawa Archive

Profile

Name: Takashi Kotegawa (小手川 隆)

Handle: B.N.F (B-N-F)

Born: March 5, 1978, Ichikawa, Chiba

Education: Nihon University, Faculty of Law (Dropout)

Key Asset: AKIBA Cultures ZONE (formerly Chomp Chomp Akihabara) - Sold approx 2018

Estimated Wealth Trajectory

2000: 1.6 Million JPY - Initial Capital from part-time jobs

2001: 61 Million JPY - The Bear Market Divergence Strategy begins

2002: 96 Million JPY - Compounding small gains

2003: 270 Million JPY - Market recovery begins

2004: 1.1 Billion JPY - First billion yen milestone

2005: 8.0 Billion JPY - The J-Com Shock Trade (+2.2B yen)

2006: 15.7 Billion JPY - Featured on TV (”Gaia no Yoake”)

2007: 18.5 Billion JPY - Continued growth despite volatility

2008: 21.8 Billion JPY - Lehman Loss (-700M), Real Estate Purchase (9B)

2018: ~30.0 Billion+ JPY - Sale of Akihabara building

2025: Unknown (Likely >30 Billion Yen)

Strategy Summary

25-Day Moving Average: Primary baseline for value

Deviation Rate (Kairi): The buy signal; specific % drops trigger entry

Volume: Confirmation of panic/capitulation

RSI: Secondary confirmation of oversold conditions

Sector Correlation: Buying the “Laggard” in a moving sector

Famous Trades

J-Com (2005): The 2 billion yen windfall from the Mizuho error.

Lehman Brothers (2008): Bought the dip just before bankruptcy. Lost ~700 million yen. Punched two monitors.

Softbank (2005/2014): Repeatedly traded swings in Masayoshi Son’s volatile empire.

Sources

Purple Trading. “Legends of Trading: Mysterious Trader from Japan - Takashi Kotegawa”.

Japan Times. “Day traders fight for respect in Japan’s tough market” (Coverage of CIS and B.N.F).

Pocket Option. “Takashi Kotegawa Review: The Legacy of a Trading Legend”.

Binance Square. “Meet BNF — The Japanese Day Trading Legend”.

Ultima Markets Academy. “Trading Strategy of BNF Takashi Kotegawa”.

Wikipedia (FR). “B.N.F (Takashi Kotegawa)”.

Reddit r/Japan & r/JapanFinance. Discussions on Takashi Kotegawa’s whereabouts and real estate holdings.

YouTube. “Gaia no Yoake” (Dawn of Gaia) - TV Tokyo documentary featuring B.N.F (2006).

Fantastic deep dive into BNF's strategy, the 25-day MA deviation approach is brillant for systematic mean reversion. That J-Com trade epitomizes pattern recognition under pressure, most traders froze while he calculated probabilities. The Akihabara building purchase was a savvy wealth preservation move when scaling became an obstacle to day trading.